Labeling requirements for CBD-infused wine products are an important aspect of the legal regulations surrounding CBD-infused products. When it comes to selling CBD-infused wine, companies must adhere to strict guidelines set forth by regulatory authorities.

These labeling requirements typically include information such as the amount of CBD present in the product, the source of the CBD, and any potential side effects or warnings associated with consuming the product. Additionally, labels must be clear and accurate so that consumers can make informed decisions about their purchase.

Failure to comply with labeling requirements for CBD-infused wine products can result in fines or other penalties for companies. It is crucial for businesses in this industry to stay up-to-date on the latest regulations and ensure that their products are in full compliance.

Overall, labeling requirements play a crucial role in ensuring transparency and consumer safety when it comes to CBD-infused wine products. By following these guidelines, companies can help build trust with their customers and navigate the complex regulatory landscape surrounding CBD-infused products.

When it comes to producing CBD wine, there are certain legal regulations that need to be followed. One of the key aspects is obtaining the necessary licensing and permits to ensure that the product is being produced in compliance with the law.

In order to produce CBD wine, you will likely need a license from your state's alcohol regulatory agency as well as any other relevant permits required for producing and selling alcoholic beverages. This could include a winery license, a distributor license, or a retailer license depending on your business model.

Additionally, because CBD is derived from cannabis, you may also need to obtain a license from your state's cannabis regulatory agency if you are using CBD derived from marijuana rather than hemp. This is important to ensure that you are following all regulations surrounding the production and sale of cannabis products.

It is crucial to do thorough research and consult with legal experts to understand the specific licensing and permitting requirements for producing CBD wine in your area. Failure to obtain the necessary licenses and permits could result in fines, penalties, or even criminal charges.

By taking the time to navigate the legal landscape surrounding CBD-infused products and obtaining the proper licensing and permits, you can ensure that your CBD wine business operates within the boundaries of the law and avoids any potential legal issues.

When it comes to CBD-infused wines, testing and quality control regulations are crucial in ensuring the safety and efficacy of these products. The legal landscape surrounding CBD-infused products can be complex, with different regulations varying from state to state.

In order to comply with these regulations, manufacturers of CBD-infused wines must adhere to strict testing protocols to ensure that their products contain the advertised amount of CBD and do not exceed the legal limit of THC. This is important not only for consumer safety but also for maintaining the integrity of the industry as a whole.

Quality control measures are equally important in ensuring that CBD-infused wines meet certain standards of purity and consistency. This includes regular testing for contaminants such as pesticides, heavy metals, and solvents, as well as monitoring factors such as flavor profile and shelf stability.

By following these testing and quality control regulations, manufacturers can ensure that their CBD-infused wines are safe, effective, and compliant with all relevant laws. This not only protects consumers but also helps to build trust in the burgeoning market for CBD-infused products.

Advertising restrictions for CBD wine products can be complex and vary depending on the country or state in which they are being sold. In many places, there are strict guidelines in place to ensure that advertising for CBD-infused products is not misleading or targeting minors.

For example, in the United States, the Federal Trade Commission has specific regulations regarding health claims made about CBD products. This means that companies selling CBD wine cannot make unsubstantiated claims about the health benefits of their products without facing potential legal consequences.

Similarly, in countries like Canada and Australia, advertising for cannabis products including CBD must comply with strict regulations set forth by their respective health regulatory agencies. These regulations often prohibit advertising that could appeal to minors or promote excessive consumption of alcohol or cannabis.

Additionally, some states in the US have further restrictions on advertising for CBD products if they contain more than a certain amount of THC. For example, California has specific requirements for labeling and packaging of cannabis products to ensure they are not marketed towards children or youth.

Overall, it is crucial for companies selling CBD wine products to be aware of and comply with all advertising restrictions in order to avoid potential legal issues. By following these regulations, companies can ensure that their marketing efforts are both effective and responsible.

|

|

| Type | Alcoholic beverage |

|---|---|

| Alcohol by volume | 5–16%[1] |

| Ingredients | Varies; see Winemaking |

| Variants | |

Wine is an alcoholic drink made from fermented fruit. Yeast consumes the sugar in the fruit and converts it to ethanol and carbon dioxide, releasing heat in the process. Wine is most often made from grapes, and the term "wine" generally refers to grape wine when used without any qualification. Even so, wine can be made from a variety of fruit crops, including plum, cherry, pomegranate, blueberry, currant, and elderberry.

Different varieties of grapes and strains of yeasts are major factors in different styles of wine. These differences result from the complex interactions between the biochemical development of the grape, the reactions involved in fermentation, the grape's growing environment (terroir), and the wine production process. Many countries enact legal appellations intended to define styles and qualities of wine. These typically restrict the geographical origin and permitted varieties of grapes, as well as other aspects of wine production.

Wine has been produced for thousands of years. The earliest evidence of wine is from the present-day Georgia (6000 BCE), Persia (5000 BCE), Italy, and Armenia (4000 BCE). New World wine has some connection to alcoholic beverages made by the indigenous peoples of the Americas but is mainly connected to later Spanish traditions in New Spain.[2][3] Later, as Old World wine further developed viticulture techniques, Europe would encompass three of the largest wine-producing regions. The top five wine producing countries of 2023 were Italy, France, Spain, the United States and China.

Wine has long played an important role in religion. Red wine was associated with blood by the ancient Egyptians,[4] and was used by both the Greek cult of Dionysus and the Romans in their Bacchanalia; Judaism also incorporates it in the Kiddush, and Christianity in the Eucharist. Egyptian, Greek, Roman, and Israeli wine cultures are still connected to these ancient roots. Similarly the largest wine regions in Italy, Spain, and France have heritages in connection to sacramental wine, likewise, viticulture traditions in the Southwestern United States started within New Spain as Catholic friars and monks first produced wines in New Mexico and California.[5][6][7]

The earliest known traces of wine are from Georgia (c. 6000 BCE),[3][2] Persia (c. 5000 BCE),[8][9] Armenia (c. 4100 BCE),[10] and Sicily (c. 4000 BCE).[11] Wine reached the Mediterranean Basin in the early Bronze Age and was consumed and celebrated by ancient civilizations like ancient Greece and Rome. Throughout history, wine has been consumed for its intoxicating effects.[12]

The earliest archaeological and archaeobotanical evidence for grape wine and viniculture, dating to 6000–5800 BCE was found on the territory of modern Georgia.[13][14] Both archaeological and genetic evidence suggest that the earliest production of wine outside of Georgia was relatively later, likely having taken place elsewhere in the Southern Caucasus (which encompasses Armenia, Georgia and Azerbaijan), or the West Asian region between Eastern Turkey, and northern Iran.[15][16] The earliest known winery, from 4100 BCE, is the Areni-1 winery in Armenia.[10][17]

A 2003 report by archaeologists indicates a possibility that grapes were mixed with rice to produce fermented drinks in ancient China in the early years of the seventh millennium BCE. Pottery jars from the Neolithic site of Jiahu, Henan, contained traces of tartaric acid and other organic compounds commonly found in wine. However, other fruits indigenous to the region, such as hawthorn, cannot be ruled out.[18][19] If these drinks, which seem to be the precursors of rice wine, included grapes rather than other fruits, they would have been any of the several dozen indigenous wild species in China, rather than Vitis vinifera, which was introduced 6000 years later.[18][20][21][22][3]

In 2020, a 2,600-year-old well-preserved Phoenician wine press was excavated at Tell el-Burak, south of Sidon in Lebanon, probably devoted to making wine for trading in their colonies.[23] The spread of wine culture westwards was most probably due to the Phoenicians, who spread outward from a base of city-states along the Mediterranean coast centered around modern day Lebanon (as well as including small parts of Israel/Palestine and coastal Syria);[24] however, the Nuragic culture in Sardinia already had a custom of consuming wine before the arrival of the Phoenicians.[25][26] The wines of Byblos were exported to Egypt during the Old Kingdom and then throughout the Mediterranean. Evidence for this includes two Phoenician shipwrecks from 750 BCE, found with their cargoes of wine still intact.[27] As the first great traders in wine (cherem), the Phoenicians seem to have protected it from oxidation with a layer of olive oil, followed by a seal of pinewood and resin, similar to retsina.

The earliest remains of Apadana Palace in Persepolis dating back to 515 BCE include carvings depicting soldiers from the Achaemenid Empire subject nations bringing gifts to the Achaemenid king, among them Armenians bringing their famous wine.

Literary references to wine are abundant in Homer (8th century BCE, but possibly relating earlier compositions), Alkman (7th century BCE), and others. In ancient Egypt, six of 36 wine amphoras were found in the tomb of King Tutankhamun bearing the name "Kha'y", a royal chief vintner. Five of these amphoras were designated as originating from the king's personal estate, with the sixth from the estate of the royal house of Aten.[28] Traces of wine have also been found in central Asian Xinjiang in modern-day China, dating from the second and first millennia BCE.[29]

The first known mention of grape-based wines in India is from the late 4th-century BCE writings of Chanakya, the chief minister of Emperor Chandragupta Maurya. In his writings, Chanakya condemns the use of alcohol while chronicling the emperor and his court's frequent indulgence of a style of wine known as madhu.[30]

The ancient Romans planted vineyards near garrison towns so wine could be produced locally rather than shipped over long distances. Some of these areas are now world-renowned for wine production.[31] The Romans discovered that burning sulfur candles inside empty wine vessels kept them fresh and free from a vinegar smell, due to the antioxidant effects of sulfur dioxide.[32] In medieval Europe, the Roman Catholic Church supported wine because the clergy required it for the Mass. Monks in France made wine for years, aging it in caves.[33] An old English recipe that survived in various forms until the 19th century calls for refining white wine from bastard—bad or tainted bastardo wine.[34]

Later, the descendants of the sacramental wine were refined for a more palatable taste. This gave rise to modern viticulture in French wine, Italian wine, Spanish wine, and these wine grape traditions were brought into New World wine. For example, Mission grapes were brought by Franciscan monks to New Mexico in 1628 beginning the New Mexico wine heritage, these grapes were also brought to California which started the California wine industry. Thanks to Spanish wine culture, these two regions eventually evolved into the oldest and largest producers, respectively, of wine of the United States.[35][36][37] Viking sagas earlier mentioned a fantastic land filled with wild grapes and high-quality wine called precisely Vinland.[38][unreliable source?] Prior to the Spanish establishing their American wine grape traditions in California and New Mexico, both France and Britain had unsuccessfully attempted to establish grapevines in Florida and Virginia respectively.[39]

In East Asia, the first modern wine industry was Japanese wine, developed in 1874 after grapevines were brought back from Europe.[40]

The English word "wine" comes from the Proto-Germanic *winam, an early borrowing from the Latin vinum, Georgian ღვინრ(ghvee-no), "wine", itself derived from the Proto-Indo-European stem *uoin-a- (cf. Armenian: Õ£Õ«Õ¶Õ«, gini; Ancient Greek: οἶνος oinos; Hittite: uiian(a)-).[41] The earliest attested terms referring to wine[citation needed] are the Mycenaean Greek ð€•ð€¶ð€ºð„€ð€šð€º me-tu-wo ne-wo (*μÎθυÏος νÎÏῳ),[42] meaning "in (the month)" or "(festival) of the new wine", and ð€ºð€œð€·ð€´ð€¯ wo-no-wa-ti-si,[43] meaning "wine garden", written in Linear B inscriptions.[44][45]

The ultimate Indo-European origin of the word is the subject of some continued debate. Some scholars have noted the similarities between the words for wine in Indo-European languages (e.g. Armenian gini, Latin vinum, Ancient Greek οἶνος, Russian вино [vʲɪˈno]), Kartvelian (e.g. Georgian ღვინრ[ˈɣvino]), and Semitic (*wayn; Hebrew יין [jajin]), pointing to the possibility of a common origin of the word denoting "wine" in these language families.[46] The Georgian word goes back to Proto-Kartvelian *É£wino-,[47] which is either a borrowing from Proto-Indo-European[47][48] or the lexeme was specifically borrowed from Proto-Armenian *ɣʷeinyo-, whence Armenian gini.[49][50][51][52][47][verification needed] An alternative hypothesis by Fähnrich supposes *É£wino-, a native Kartvelian word derived from the verbal root *É£un- ('to bend').[53][54] All these theories place the origin of the word in the same geographical location, South Caucasus, that has been established based on archeological and biomolecular studies as the origin of viticulture.[citation needed]

Wine is made in many ways from different fruits, with grapes being the most common.

The type of grape used and the amount of skin contact while the juice is being extracted determines the color and general style of the wine. The color has no relation to a wine's sweetness—all may be made sweet or dry.

| Long contact with grape skins | Short contact with grape skins | No contact with grape skins | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Red grapes | Red wine | Rosé wine | White wine |

| White grapes | Orange wine |

Red wine gains its color and flavor (notably, tannins) from the grape skin, by allowing the grapes to soak in the extracted juice. Red wine is made from dark-colored red grape varieties. The actual color of the wine can range from violet, typical of young wines, through red for mature wines, to brown for older red wines. The juice from most red grapes is actually greenish-white; the red color comes from anthocyanins present in the skin of the grape. A notable exception is the family of rare teinturier varieties, which actually have red flesh and produce red juice.

To make white wine, grapes are pressed quickly with the juice immediately drained away from the grape skins. The grapes used are typically white grape varieties, though red grapes may be used if the winemaker is careful not to let the skin stain the wort during the separation of the pulp-juice. For example, pinot noir (a red grape) is commonly used in champagne.

Dry (low sugar) white wine is the most common, derived from the complete fermentation of the juice, however sweet white wines such as Moscato d'Asti are also made.

A rosé wine gains color from red grape skins, but not enough to qualify it as a red wine. It may be the oldest known type of wine, as it is the most straightforward to make with the skin contact method. The color can range from a pale orange to a vivid near-purple, depending on the varietals used and wine-making techniques.

There are three primary ways to produce rosé wine: Skin contact (allowing dark grape skins to stain the wort), saignée (removing juice from the must early in fermentation and continuing fermentation of the juice separately), and blending of a red and white wine (uncommon and discouraged in most wine growing regions). Rosé wines have a wide range of sweetness levels from dry Provençal rosé to sweet White Zinfandels and blushes. Rosé wines are made from a wide variety of grapes all over the world.[55][56]

Sometimes called amber wines, these are wines made with white grapes but with the skins allowed to soak during pressing, similar to red and rosé wine production. They are notably tannic, and usually made dry.[57]

These are effervescent wines, made in any of the above styles (i.e, orange, red, rosé, white). They must undergo secondary fermentation to create carbon dioxide, which creates the bubbles.

Two common methods of accomplishing this are the traditional method, used for Cava, Champagne, and more expensive sparkling wines, and the Charmat method, used for Prosecco, Asti, and less expensive wines. A hybrid transfer method is also used, yielding intermediate results, and simple addition of carbon dioxide is used in the cheapest of wines.[58]

The bottles used for sparkling wine must be thick to withstand the pressure of the gas behind the cork, which can be up to 6 standard atmospheres (88 psi).[59]

This refers to sweet wines that have a high level of sugar remaining after fermentation. There are various ways of increasing the amount of sugar in a wine, yielding products with different strengths and names. Icewine, Port, Sauternes, Tokaji Aszú, Trockenbeerenauslese, and Vin Santo are some examples.

Wines from other fruits, such as apples and berries, are usually named after the fruit from which they are produced, and combined with the word "wine" (for example, apple wine and elderberry wine) and are generically called fruit wine or country wine (similar to French term vin de pays). Other than the grape varieties traditionally used for wine-making, most fruits naturally lack either sufficient fermentable sugars, proper amount of acidity, yeast amounts needed to promote or maintain fermentation, or a combination of these three materials. This is probably one of the main reasons why wine derived from grapes has historically been more prevalent by far than other types, and why specific types of fruit wines have generally been confined to the regions in which the fruits were native or introduced for other reasons.[citation needed]

Mead, also called honey wine, is created by fermenting honey with water, sometimes with various fruits, spices, grains, or hops. As long as the primary substance fermented is honey, the drink is considered mead.[60] Mead was produced in ancient history throughout Europe, Africa and Asia,[61] and was known in Europe before grape wine.[62]

Other drinks called "wine", such as barley wine and rice wine (e.g. sake, huangjiu and cheongju), are made from starch-based materials and resemble beer more than traditional wine, while ginger wine is fortified with brandy. In these latter cases, the term "wine" refers to the similarity in alcohol content rather than to the production process.[63] The commercial use of the English word "wine" (and its equivalent in other languages) is protected by law in many jurisdictions.[64]

Wine is usually made from one or more varieties of the European species Vitis vinifera,[65] such as Pinot noir, Chardonnay, Cabernet Sauvignon, Gamay and Merlot. When one of these varieties is used as the predominant grape (usually defined by law as a minimum of 75% to 85%), the result is a "varietal" as opposed to a "blended" wine. Blended wines are not necessarily inferior to varietal wines, rather they are a different style of wine-making.[66]

Wine can also be made from other species of grape or from hybrids, created by the genetic crossing of two species. V. labrusca (of which the Concord grape is a cultivar), V. aestivalis, V. rupestris, V. rotundifolia and V. riparia are native North American grapes usually grown to eat fresh or for grape juice, jam, or jelly, and only occasionally made into wine.[citation needed]

Hybridization is different from grafting. Most of the world's vineyards are planted with European Vitis vinifera vines that have been grafted onto North American species' rootstock, a common practice due to their resistance to phylloxera, a root louse that eventually kills the vine.[65] In the late 19th century, most of Europe's vineyards (excluding some of the driest in the south) were devastated by the infestation, leading to widespread vine deaths and eventual replanting. Grafting is done in every wine-producing region in the world except in Argentina and the Canary Islands – the only places not yet exposed to the insect.[citation needed]

In the context of wine production, terroir is a concept that encompasses the varieties of grapes used, elevation and shape of the vineyard, type and chemistry of soil, climate and seasonal conditions, and the local yeast cultures.[67] The range of possible combinations of these factors can result in great differences among wines, influencing the fermentation, finishing, and aging processes as well. Many wineries use growing and production methods that preserve or accentuate the aroma and taste influences of their unique terroir.[68] However, flavor differences are less desirable for producers of mass-market table wine or other cheaper wines, where consistency takes precedence. Such producers try to minimize differences in sources of grapes through production techniques such as micro-oxygenation, tannin filtration, cross-flow filtration, thin-film evaporation, and spinning cones.[69]

About 700 grapes go into one bottle of wine, approximately 2.6 pounds.[70]

Wine grapes grow almost exclusively between 30 and 50 degrees latitude north and south of the equator. The world's southernmost vineyards are in the Central Otago region of New Zealand's South Island near the 45th parallel south,[71] and the northernmost are in Flen, Sweden, just north of the 59th parallel north.[72]

The UK was the world's largest importer of wine in 2007.[73]

| Rank | Country | Production (million hecolitres)[74] |

Production (% of world)[74] |

Exports (million hecolitres)[75] | Export market share (% of value in US$)[76] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 48.0 | 20.2% | 12.7 | 33.3% | |

| 2 | 38.3 | 16.1% | 21.4 | 21.6% | |

| 3 | 28.3 | 11.9% | 20.8 | 8.2% | |

| 4 | 24.3* | 10.2%* | 2.1 | 3.2% | |

| 5 | 11.0 | 4.6% | 6.8 | 3.9% | |

| 6 | 9.6 | 4.1% | 6.2 | 3.6% | |

| 7 | 9.3 | 3.9% | 3.5 | 1.6% | |

| 8 | 8.8 | 3.7% | 2.0 | 1.7% | |

| 9 | 8.6 | 3.6% | 3.3 | 2.9% | |

| 10 | 7.5 | 3.2% | 3.2 | 2.6% | |

| World | 237.3 | * Estimated | |||

Regulations govern the classification and sale of wine in many regions of the world. European wines tend to be classified by region (e.g. Bordeaux, Rioja and Chianti), while non-European wines are most often classified by grape (e.g. Pinot noir and Merlot). Market recognition of particular regions has recently been leading to their increased prominence on non-European wine labels. Examples of recognized non-European locales include Napa Valley, Santa Clara Valley, Sonoma Valley, Anderson Valley, and Mendocino County in California; Willamette Valley and Rogue Valley in Oregon; Columbia Valley in Washington; Barossa Valley in South Australia; Hunter Valley in New South Wales; Luján de Cuyo in Argentina; Vale dos Vinhedos in Brazil; Hawke's Bay and Marlborough in New Zealand; Central Valley in Chile; and in Canada, the Okanagan Valley of British Columbia, and the Niagara Peninsula and Essex County regions of Ontario are the three largest producers.

Some blended wine names are marketing terms whose use is governed by trademark law rather than by specific wine laws. For example, Meritage is generally a Bordeaux-style blend of Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot, but may also include Cabernet Franc, Petit Verdot, and Malbec. Commercial use of the term Meritage is allowed only via licensing agreements with the Meritage Association.

France has various appellation systems based on the concept of terroir, with classifications ranging from Vin de Table ("table wine") at the bottom, through Vin de Pays and Appellation d'Origine Vin Délimité de Qualité Supérieure (AOVDQS), up to Appellation d'Origine Contrôlée (AOC) or similar, depending on the region.[77][78] Portugal has developed a system resembling that of France and, in fact, pioneered this concept in 1756 with a royal charter creating the Demarcated Douro Region and regulating the production and trade of wine.[79] Germany created a similar scheme in 2002, although it has not yet achieved the authority of the other countries' classification systems.[80][81] Spain, Greece and Italy have classifications based on a dual system of region of origin and product quality.[82]

New World wines—those made outside the traditional wine regions of Europe—are usually classified by grape rather than by terroir or region of origin, although there have been unofficial attempts to classify them by quality.[83][84][needs update]

According to Canadian Food and Drug Regulations, wine in Canada is an alcoholic drink that is produced by the complete or partial alcoholic fermentation of fresh grapes, grape must, products derived solely from fresh grapes, or any combination of them. There are many materials added during the course of the manufacture, such as yeast, concentrated grape juice, dextrose, fructose, glucose or glucose solids, invert sugar, sugar, or aqueous solutions. Calcium sulphate in such quantity that the content of soluble sulphates in the finished wine shall not exceed 0.2 percent weight by volume calculated as potassium sulphate. Calcium carbonate in such quantity that the content of tartaric acid in the finished wine shall not be less than 0.15 percent weight by volume. Also, sulphurous acid, including salts thereof, in such quantity that its content in the finished wine shall not exceed 70 parts per million in the free state, or 350 parts per million in the combined state, calculated as sulphur dioxide. Caramel, amylase and pectinase at a maximum level of use consistent with good manufacturing practice. Prior to final filtration may be treated with a strongly acid cation exchange resin in the sodium ion form, or a weakly basic anion exchange resin in the hydroxyl ion form.[85]

For wines produced in the European Union, if a bottle of wine indicates a vintage, then at least 85% of the grapes must have been harvested in that year.[86] In the United States, for a wine to be vintage-dated and labeled with a country of origin or American Viticultural Area (AVA; e.g., Sonoma Valley), 95% of its volume must be from grapes harvested in that year.[87] If a wine is not labeled with a country of origin or AVA the percentage requirement is lowered to 85%.[87]

Vintage wines are generally bottled in a single batch so that each bottle will have a similar taste. Climate's impact on the character of a wine can be significant enough to cause different vintages from the same vineyard to vary dramatically in flavor and quality.[88][unreliable source?] Thus, vintage wines are produced to be individually characteristic of the particular vintage and to serve as the flagship wines of the producer. Superior vintages from reputable producers and regions will often command much higher prices than their average ones. Some vintage wines (e.g. Brunello), are only made in better-than-average years.

For consistency, non-vintage wines can be blended from more than one vintage, which helps wine-makers sustain a reliable market image and maintain sales even in bad years.[89][90] One recent study suggests that for the average wine drinker, the vintage year may not be as significant for perceived quality as had been thought, although wine connoisseurs continue to place great importance on it.[91]

Most wines are sold in glass bottles and sealed with corks[citation needed] (50% of which come from Portugal).[92] An increasing number of wine producers have been using alternative closures such as screwcaps and synthetic plastic "corks". Although alternative closures are less expensive and reduce the risk of cork taint, they have been blamed for such problems as excessive reduction.[93]

Some wines are packaged in thick plastic bags within corrugated fiberboard boxes, and are called "box wines", or "cask wine". Tucked inside the package is a tap affixed to the bag in box, or bladder, that is later extended by the consumer for serving the contents. Box wine can stay acceptably fresh for up to a month after opening because the bladder collapses as wine is dispensed, limiting contact with air and, thus, slowing the rate of oxidation. In contrast, bottled wine oxidizes more rapidly after opening because of the increasing ratio of air to wine as the contents are dispensed; it can degrade considerably in a few days. Canned wine is one of the fastest-growing forms of alternative wine packaging on the market.[94]

Environmental considerations of wine packaging reveal the benefits and drawbacks of both bottled and box wines. The glass used to make bottles is a nontoxic, naturally occurring substance that is completely recyclable, whereas the plastics used for box-wine containers are typically much less environmentally friendly. However, wine-bottle manufacturers have been cited for Clean Air Act violations. A New York Times editorial suggested that box wine, being lighter in package weight, has a reduced carbon footprint from its distribution; however, box-wine plastics, even though possibly recyclable, can be more labor-intensive (and therefore expensive) to process than glass bottles. In addition, while a wine box is recyclable, its plastic bladder most likely is not.[95] Some people are drawn to canned wine due to its portability and recyclable packaging.[94]

Some wine is sold in stainless steel kegs and is referred to as wine on tap.

Incidents of fraud, such as mislabeling the origin or quality of wines, have resulted in regulations on labeling. "Wine scandals" that have received media attention include:

Wine tasting is the sensory examination and evaluation of wine. Wines contain many chemical compounds similar or identical to those in fruits, vegetables, and spices. The sweetness of wine is determined by the amount of residual sugar in the wine after fermentation, relative to the acidity present in the wine. Dry wine, for example, has only a small amount of residual sugar. Some wine labels suggest opening the bottle and letting the wine "breathe" for a couple of hours before serving, while others recommend drinking it immediately. Decanting (the act of pouring a wine into a special container just for breathing) is a controversial subject among wine enthusiasts. In addition to aeration, decanting with a filter allows the removal of bitter sediments that may have formed in the wine. Sediment is more common in older bottles, but aeration may benefit younger wines.[101]

During aeration, a younger wine's exposure to air often "relaxes" the drink, making it smoother and better integrated in aroma, texture, and flavor. Older wines generally fade (lose their character and flavor intensity) with extended aeration.[102] Despite these general rules, breathing does not necessarily benefit all wines. Wine may be tasted as soon as the bottle is opened to determine how long it should be aerated, if at all.[103][better source needed] When tasting wine, individual flavors may also be detected, due to the complex mix of organic molecules (e.g. esters and terpenes) that grape juice and wine can contain. Experienced tasters can distinguish between flavors characteristic of a specific grape and flavors that result from other factors in wine-making. Typical intentional flavor elements in wine—chocolate, vanilla, or coffee—are those imparted by aging in oak casks rather than the grape itself.[104]

Vertical and horizontal tasting involves a range of vintages within the same grape and vineyard, or the latter in which there is one vintage from multiple vineyards. "Banana" flavors (isoamyl acetate) are the product of yeast metabolism, as are spoilage aromas such as "medicinal" or "Band-Aid" (4-ethylphenol), "spicy" or "smoky" (4-ethylguaiacol),[105] and rotten egg (hydrogen sulfide).[106] Some varieties can also exhibit a mineral flavor due to the presence of water-soluble salts as a result of limestone's presence in the vineyard's soil. Wine aroma comes from volatile compounds released into the air.[107] Vaporization of these compounds can be accelerated by twirling the wine glass or serving at room temperature. Many drinkers prefer to chill red wines that are already highly aromatic, like Chinon and Beaujolais.[108]

The ideal temperature for serving a particular wine is a matter of debate by wine enthusiasts and sommeliers, but some broad guidelines have emerged that will generally enhance the experience of tasting certain common wines. White wine should foster a sense of coolness, achieved by serving at "cellar temperature" (13 °C or 55 °F). Light red wines drunk young should also be brought to the table at this temperature, where they will quickly rise a few degrees. Red wines are generally perceived best when served chambré ("at room temperature"). However, this does not mean the temperature of the dining room—often around 21 °C (70 °F)—but rather the coolest room in the house and, therefore, always slightly cooler than the dining room itself. Pinot noir should be brought to the table for serving at 16 °C (61 °F) and will reach its full bouquet at 18 °C (64 °F). Cabernet Sauvignon, zinfandel, and Rhone varieties should be served at 18 °C (64 °F) and allowed to warm on the table to 21 °C (70 °F) for best aroma.[109]

Outstanding vintages from the best vineyards may sell for thousands of dollars per bottle, though the broader term "fine wine" covers those typically retailing in excess of US$30–50.[110] "Investment wines" are considered by some to be Veblen goods: those for which demand increases rather than decreases as their prices rise. Particular selections such as "Verticals", which span multiple vintages of a specific grape and vineyard, may be highly valued. The most notable was a Château d'Yquem 135-year vertical containing every vintage from 1860 to 2003 sold for $1.5 million. The most common wines purchased for investment include those from Bordeaux and Burgundy; cult wines from Europe and elsewhere; and vintage port. Characteristics of highly collectible wines include:

Investment in fine wine has attracted those who take advantage of their victims' relative ignorance of this wine market sector.[111] Such wine fraudsters often profit by charging excessively high prices for off-vintage or lower-status wines from well-known wine regions, while claiming that they are offering a sound investment unaffected by economic cycles. As with any investment, thorough research is essential to making an informed decision.

| Country | Liters per capita |

|---|---|

| 8.14 | |

| 6.65 | |

| 6.38 | |

| 5.80 | |

| 5.69 | |

| 5.10 | |

| 5.10 | |

| 4.94 | |

| 4.67 | |

| 4.62 |

Wine is a popular and important drink that accompanies and enhances a wide range of cuisines, from the simple and traditional stews to the most sophisticated and complex haute cuisines. Wine is often served with dinner. Sweet dessert wines may be served with the dessert course. In fine restaurants in Western countries, wine typically accompanies dinner. At a restaurant, patrons are helped to make good food-wine pairings by the restaurant's sommelier or wine waiter. Individuals dining at home may use wine guides to help make food–wine pairings. Wine is also drunk without the accompaniment of a meal in wine bars or with a selection of cheeses (at a wine and cheese party). Wines are also used as a theme for organizing various events such as festivals around the world; the city of Kuopio in North Savonia, Finland is known for its annual Kuopio Wine Festivals (Kuopion viinijuhlat).[115]

Wine is important in cuisine not just for its value as a drink, but as a flavor agent, primarily in stocks and braising, since its acidity lends balance to rich savoury or sweet dishes.[116] Wine sauce is an example of a culinary sauce that uses wine as a primary ingredient.[117] Natural wines may exhibit a broad range of alcohol content, from below 9% to above 16% ABV, with most wines being in the 12.5–14.5% range.[118] Fortified wines (usually with brandy) may contain 20% alcohol or more.

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy | 355 kJ (85 kcal) | ||||

|

2.6 g

|

|||||

| Sugars | 0.6 g | ||||

|

0.0 g

|

|||||

|

0.1 g

|

|||||

|

|||||

| Other constituents | Quantity | ||||

| Alcohol (ethanol) | 10.6 g | ||||

|

10.6 g alcohol is 13%vol.

100 g wine is approximately 100 ml (3.4 fl oz.) Sugar and alcohol content can vary. |

|||||

Wine contains ethyl alcohol, the chemical in beer and distilled spirits. The effects of wine depend on the amount consumed, the span of time over which consumption occurs, and the amount of alcohol in the wine, among other factors. Drinking enough to reach a blood alcohol concentration (BAC) of 0.03%-0.12% may cause an overall improvement in mood, increase self-confidence and sociability, decrease anxiety, flushing of the face, and impair judgment and fine motor coordination. A BAC of 0.09% to 0.25% causes lethargy, sedation, balance problems and blurred vision. A BAC from 0.18% to 0.30% causes profound confusion, impaired speech (e.g. slurred speech), staggering, dizziness and vomiting. A BAC from 0.25% to 0.40% causes stupor, unconsciousness, anterograde amnesia, vomiting, and death may occur due to respiratory depression and inhalation of vomit during unconsciousness. A BAC from 0.35% to 0.80% causes coma, life-threatening respiratory depression and possibly fatal alcohol poisoning. The operation of vehicles or machinery while drunk can increase the risk of accident, and many countries have laws against drinking and driving. The social context and quality of wine can affect the mood and emotions.[119]

The main active ingredient of wine is ethanol. A 2016 systematic review and meta-analysis found that moderate ethanol consumption brought no mortality benefit compared with lifetime abstention from ethanol consumption.[120] A systematic analysis of data from the Global Burden of Disease study found that consumption of ethanol increases the risk of cancer and increases the risk of all-cause mortality, and that the most healthful dose of ethanol is zero consumption.[121] Some studies have concluded that drinking small quantities of alcohol (less than one drink daily in women and two drinks daily in men) is associated with a decreased risk of heart disease, stroke, diabetes mellitus, and early death.[122] Ethanol consumption increases the risk of heart disease, high blood pressure, atrial fibrillation, and stroke. Some studies that reported benefits of moderate ethanol consumption erred by lumping former drinkers and life-long abstainers into a single group of nondrinkers, hiding the health benefits of life-long abstention from ethanol.[122] Risk is greater in younger people due to binge drinking which may result in violence or accidents.[122] About 3.3 million deaths (5.9% of all deaths) annually are due to ethanol use.[123][124][125]

Alcohol use disorder is the inability to stop or control alcohol use despite harmful consequences to health, job, or relationships; alternative terms include alcoholism, alcohol abuse, alcohol dependence, or alcohol addiction.[126][127][128][129][130] and alcohol use is the third leading cause of early death in the United States.[122] No professional medical association recommends that people who are nondrinkers should start drinking wine.[122][131]

Excessive consumption of alcohol can cause liver cirrhosis and alcoholism.[132] The American Heart Association "cautions people NOT to start drinking ... if they do not already drink alcohol. Consult your doctor on the benefits and risks of consuming alcohol in moderation."[133]

Although red wine contains more of the stilbene resveratrol and of other polyphenols than white wine, the evidence for a cardiac health benefit is of poor quality and at most, the benefit is trivial.[134][135][136] Grape skins naturally produce resveratrol in response to fungal infection, including exposure to yeast during fermentation. White wine generally contains lower levels of the chemical as it has minimal contact with grape skins during this process.[137]

Wine cellars, or wine rooms, if they are above-ground, are places designed specifically for the storage and aging of wine. Fine restaurants and some private homes have wine cellars. In an active wine cellar, temperature and humidity are maintained by a climate-control system. Passive wine cellars are not climate-controlled, and so must be carefully located. Because wine is a natural, perishable food product, all types—including red, white, sparkling, and fortified—can spoil when exposed to heat, light, vibration or fluctuations in temperature and humidity. When properly stored, wines can maintain their quality and in some cases improve in aroma, flavor, and complexity as they age. Some wine experts contend that the optimal temperature for aging wine is 13 °C (55 °F),[138] others 15 °C (59 °F).[139]

Wine refrigerators offer a smaller alternative to wine cellars and are available in capacities ranging from small, 16-bottle units to furniture-quality pieces that can contain 500 bottles. Wine refrigerators are not ideal for aging, but rather serve to chill wine to the proper temperature for drinking. These refrigerators keep the humidity low (usually under 50%), below the optimal humidity of 50% to 70%. Lower humidity levels can dry out corks over time, allowing oxygen to enter the bottle, which reduces the wine's quality through oxidation.[140] While some types of alcohol are sometimes stored in the freezer, such as vodka, it is not possible to safely freeze wine in the bottle, as there is insufficient room for it to expand as it freezes and the bottle will usually crack. Certain shapes of bottle may allow the cork to be pushed out by the ice, but if the bottle is frozen on its side, the wine in the narrower neck will invariably freeze first, preventing this.

There are a large number of occupations and professions that are part of the wine industry, ranging from the individuals who grow the grapes, prepare the wine, bottle it, sell it, assess it, market it and finally make recommendations to clients and serve the wine.

| Name | Description |

|---|---|

| Cellar master | A person in charge of a wine cellar |

| Cooper | A craftsperson of wooden barrels and casks. A cooperage is a facility that produces such casks |

| Négociant | A wine merchant who purchases the product of smaller growers or wine-makers to sell them under its own name |

| Oenologist | A wine scientist or wine chemist; a student of oenology. In the 2000s, BSc degrees in oenology and viticulture are available. A wine-maker may be trained as an oenologist, but often hires one as a consultant |

| Sommelier | Also called a "wine steward", this is a specialist wine expert in charge of developing a restaurant's wine list, educating the staff about wine, and assisting customers with their selections (especially food–wine pairings) |

| Vintner or winemaker | A wine producer; a person who makes wine |

| Viticulturist | A specialist in the science of grapevines; a manager of vineyard pruning, irrigation, and pest control |

| Wine critic | A wine expert and journalist who tastes and reviews wines for books and magazines |

| Wine taster | A wine expert who tastes wines to ascertain their quality and flavour |

| Wine waiter | A restaurant or wine bar server with a basic- to mid-level knowledge of wine and food–wine pairings |

The use of wine in ancient Near Eastern and Ancient Egyptian religious ceremonies was common. Libations often included wine, and the religious mysteries of Dionysus used wine as a sacramental entheogen to induce a mind-altering state.

Baruch atah Hashem (Ado-nai) Eloheinu melech ha-olam, boray p'ree hagafen – Praised be the Lord, our God, King of the universe, Creator of the fruit of the vine.

— The blessing over wine said before consuming the drink.

Wine is an integral part of Jewish laws and traditions. The Kiddush is a blessing recited over wine or grape juice to sanctify the Shabbat. On Pesach (Passover) during the Seder, it is a Rabbinic obligation of adults to drink four cups of wine.[141] In the Tabernacle and in the Temple in Jerusalem, the libation of wine was part of the sacrificial service.[142] Note that this does not mean that wine is a symbol of blood, a common misconception that contributes to the Christian beliefs of the blood libel. "It has been one of history's cruel ironies that the blood libel—accusations against Jews using the blood of murdered gentile children for the making of wine and matzot—became the false pretext for numerous pogroms. And due to the danger, those who live in a place where blood libels occur are halachically exempted from using red wine, lest it be seized as "evidence" against them."[143]

In Christianity, wine is used in a sacred rite called the Eucharist, which originates in the Gospel account of the Last Supper (Gospel of Luke 22:19) describing Jesus sharing bread and wine with his disciples and commanding them to "do this in remembrance of me." Beliefs about the nature of the Eucharist vary among denominations (see Eucharistic theologies contrasted).

While some Christians consider the use of wine from the grape as essential for the validity of the sacrament, many Protestants also allow (or require) pasteurized grape juice as a substitute. Wine was used in Eucharistic rites by all Protestant groups until an alternative arose in the late 19th century. Methodist dentist and prohibitionist Thomas Bramwell Welch applied new pasteurization techniques to stop the natural fermentation process of grape juice. Some Christians who were part of the growing temperance movement pressed for a switch from wine to grape juice, and the substitution spread quickly over much of the United States, as well as to other countries to a lesser degree.[144] There remains an ongoing debate between some American Protestant denominations as to whether wine can and should be used for the Eucharist or allowed as an ordinary drink, with Catholics and some mainline Protestants allowing wine drinking in moderation, and some conservative Protestant groups opposing consumption of alcohol altogether.[citation needed]

The earliest viticulture tradition in the Southwestern United States starts with sacramental wine, beginning in the 1600s, with Christian friars and monks producing New Mexico wine.[145]

Alcoholic drinks, including wine, are forbidden under most interpretations of Islamic law.[146] In many Muslim countries, possession or consumption of alcoholic drinks carry legal penalties. Iran had previously had a thriving wine industry that disappeared after the Islamic Revolution in 1979.[147] In Greater Persia, mey (Persian wine) was a central theme of poetry for more than a thousand years, long before the advent of Islam. Some Alevi sects – one of the two main branches of Islam in Turkey (the other being Sunni Islam) – use wine in their religious services.[citation needed]

Certain exceptions to the ban on alcohol apply. Alcohol derived from a source other than the grape (or its byproducts) and the date[148] is allowed in "very small quantities" (loosely defined as a quantity that does not cause intoxication) under the Sunni Hanafi madhab, for specific purposes (such as medicines), where the goal is not intoxication. However, modern Hanafi scholars regard alcohol consumption as totally forbidden.[149]

...mead was known in Europe long before wine, although archaeological evidence of it is rather ambiguous. This is principally because the confirmed presence of beeswax or certain types of pollen ... is only indicative of the presence of honey (which could have been used for sweetening some other drink) – not necessarily of the production of mead.

As a general rule wine should be tasted as soon as it is opened to determine how long it might be aerated

The World Health Organization defines alcoholism as any drinking which results in problems

| Cannabis

Temporal range: Early Miocene – Present

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Common hemp | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Rosales |

| Family: | Cannabaceae |

| Genus: | Cannabis L. |

| Species[1] | |

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Cannabis |

|---|

|

Cannabis (/ˈkænÉ™bɪs/ ⓘ)[2] is a genus of flowering plants in the family Cannabaceae that is widely accepted as being indigenous to and originating from the continent of Asia.[3][4][5] However, the number of species is disputed, with as many as three species being recognized: Cannabis sativa, C. indica, and C. ruderalis. Alternatively, C. ruderalis may be included within C. sativa, or all three may be treated as subspecies of C. sativa,[1][6][7][8] or C. sativa may be accepted as a single undivided species.[9]

The plant is also known as hemp, although this term is usually used to refer only to varieties cultivated for non-drug use. Hemp has long been used for fibre, seeds and their oils, leaves for use as vegetables, and juice. Industrial hemp textile products are made from cannabis plants selected to produce an abundance of fibre.

Cannabis also has a long history of being used for medicinal purposes, and as a recreational drug known by several slang terms, such as marijuana, pot or weed. Various cannabis strains have been bred, often selectively to produce high or low levels of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), a cannabinoid and the plant's principal psychoactive constituent. Compounds such as hashish and hash oil are extracted from the plant.[10] More recently, there has been interest in other cannabinoids like cannabidiol (CBD), cannabigerol (CBG), and cannabinol (CBN).

Cannabis is a Scythian word.[11][12][13] The ancient Greeks learned of the use of cannabis by observing Scythian funerals, during which cannabis was consumed.[12] In Akkadian, cannabis was known as qunubu (ðŽ¯ðŽ«ðŽ ðŽð‚).[12] The word was adopted in to the Hebrew language as qaneh bosem (×§Ö¸× Ö¶×” בֹּשׂ×).[12]

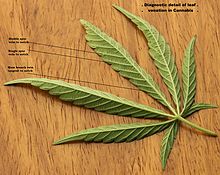

Cannabis is an annual, dioecious, flowering herb. The leaves are palmately compound or digitate, with serrate leaflets.[14] The first pair of leaves usually have a single leaflet, the number gradually increasing up to a maximum of about thirteen leaflets per leaf (usually seven or nine), depending on variety and growing conditions. At the top of a flowering plant, this number again diminishes to a single leaflet per leaf. The lower leaf pairs usually occur in an opposite leaf arrangement and the upper leaf pairs in an alternate arrangement on the main stem of a mature plant.

The leaves have a peculiar and diagnostic venation pattern (which varies slightly among varieties) that allows for easy identification of Cannabis leaves from unrelated species with similar leaves. As is common in serrated leaves, each serration has a central vein extending to its tip, but in Cannabis this originates from lower down the central vein of the leaflet, typically opposite to the position of the second notch down. This means that on its way from the midrib of the leaflet to the point of the serration, the vein serving the tip of the serration passes close by the intervening notch. Sometimes the vein will pass tangentially to the notch, but often will pass by at a small distance; when the latter happens a spur vein (or occasionally two) branches off and joins the leaf margin at the deepest point of the notch. Tiny samples of Cannabis also can be identified with precision by microscopic examination of leaf cells and similar features, requiring special equipment and expertise.[15]

All known strains of Cannabis are wind-pollinated[16] and the fruit is an achene.[17] Most strains of Cannabis are short day plants,[16] with the possible exception of C. sativa subsp. sativa var. spontanea (= C. ruderalis), which is commonly described as "auto-flowering" and may be day-neutral.

Cannabis is predominantly dioecious,[16][18] having imperfect flowers, with staminate "male" and pistillate "female" flowers occurring on separate plants.[19] "At a very early period the Chinese recognized the Cannabis plant as dioecious",[20] and the (c. 3rd century BCE) Erya dictionary defined xi 枲 "male Cannabis" and fu 莩 (or ju 苴) "female Cannabis".[21] Male flowers are normally borne on loose panicles, and female flowers are borne on racemes.[22]

Many monoecious varieties have also been described,[23] in which individual plants bear both male and female flowers.[24] (Although monoecious plants are often referred to as "hermaphrodites", true hermaphrodites – which are less common in Cannabis – bear staminate and pistillate structures together on individual flowers, whereas monoecious plants bear male and female flowers at different locations on the same plant.) Subdioecy (the occurrence of monoecious individuals and dioecious individuals within the same population) is widespread.[25][26][27] Many populations have been described as sexually labile.[28][29][30]

As a result of intensive selection in cultivation, Cannabis exhibits many sexual phenotypes that can be described in terms of the ratio of female to male flowers occurring in the individual, or typical in the cultivar.[31] Dioecious varieties are preferred for drug production, where the fruits (produced by female flowers) are used. Dioecious varieties are also preferred for textile fiber production, whereas monoecious varieties are preferred for pulp and paper production. It has been suggested that the presence of monoecy can be used to differentiate licit crops of monoecious hemp from illicit drug crops,[25] but sativa strains often produce monoecious individuals, which is possibly as a result of inbreeding.

Cannabis has been described as having one of the most complicated mechanisms of sex determination among the dioecious plants.[31] Many models have been proposed to explain sex determination in Cannabis.

Based on studies of sex reversal in hemp, it was first reported by K. Hirata in 1924 that an XY sex-determination system is present.[29] At the time, the XY system was the only known system of sex determination. The X:A system was first described in Drosophila spp in 1925.[32] Soon thereafter, Schaffner disputed Hirata's interpretation,[33] and published results from his own studies of sex reversal in hemp, concluding that an X:A system was in use and that furthermore sex was strongly influenced by environmental conditions.[30]

Since then, many different types of sex determination systems have been discovered, particularly in plants.[18] Dioecy is relatively uncommon in the plant kingdom, and a very low percentage of dioecious plant species have been determined to use the XY system. In most cases where the XY system is found it is believed to have evolved recently and independently.[34]

Since the 1920s, a number of sex determination models have been proposed for Cannabis. Ainsworth describes sex determination in the genus as using "an X/autosome dosage type".[18]

The question of whether heteromorphic sex chromosomes are indeed present is most conveniently answered if such chromosomes were clearly visible in a karyotype. Cannabis was one of the first plant species to be karyotyped; however, this was in a period when karyotype preparation was primitive by modern standards. Heteromorphic sex chromosomes were reported to occur in staminate individuals of dioecious "Kentucky" hemp, but were not found in pistillate individuals of the same variety. Dioecious "Kentucky" hemp was assumed to use an XY mechanism. Heterosomes were not observed in analyzed individuals of monoecious "Kentucky" hemp, nor in an unidentified German cultivar. These varieties were assumed to have sex chromosome composition XX.[35] According to other researchers, no modern karyotype of Cannabis had been published as of 1996.[36] Proponents of the XY system state that Y chromosome is slightly larger than the X, but difficult to differentiate cytologically.[37]

More recently, Sakamoto and various co-authors[38][39] have used random amplification of polymorphic DNA (RAPD) to isolate several genetic marker sequences that they name Male-Associated DNA in Cannabis (MADC), and which they interpret as indirect evidence of a male chromosome. Several other research groups have reported identification of male-associated markers using RAPD and amplified fragment length polymorphism.[40][28][41] Ainsworth commented on these findings, stating,

It is not surprising that male-associated markers are relatively abundant. In dioecious plants where sex chromosomes have not been identified, markers for maleness indicate either the presence of sex chromosomes which have not been distinguished by cytological methods or that the marker is tightly linked to a gene involved in sex determination.[18]

Environmental sex determination is known to occur in a variety of species.[42] Many researchers have suggested that sex in Cannabis is determined or strongly influenced by environmental factors.[30] Ainsworth reviews that treatment with auxin and ethylene have feminizing effects, and that treatment with cytokinins and gibberellins have masculinizing effects.[18] It has been reported that sex can be reversed in Cannabis using chemical treatment.[43] A polymerase chain reaction-based method for the detection of female-associated DNA polymorphisms by genotyping has been developed.[44]

Cannabis plants produce a large number of chemicals as part of their defense against herbivory. One group of these is called cannabinoids, which induce mental and physical effects when consumed.

Cannabinoids, terpenes, terpenoids, and other compounds are secreted by glandular trichomes that occur most abundantly on the floral calyxes and bracts of female plants.[46]

Cannabis, like many organisms, is diploid, having a chromosome complement of 2n=20, although polyploid individuals have been artificially produced.[47] The first genome sequence of Cannabis, which is estimated to be 820 Mb in size, was published in 2011 by a team of Canadian scientists.[48]

The genus Cannabis was formerly placed in the nettle family (Urticaceae) or mulberry family (Moraceae), and later, along with the genus Humulus (hops), in a separate family, the hemp family (Cannabaceae sensu stricto).[49] Recent phylogenetic studies based on cpDNA restriction site analysis and gene sequencing strongly suggest that the Cannabaceae sensu stricto arose from within the former family Celtidaceae, and that the two families should be merged to form a single monophyletic family, the Cannabaceae sensu lato.[50][51]

Various types of Cannabis have been described, and variously classified as species, subspecies, or varieties:[52]

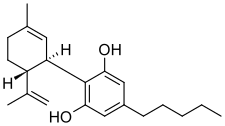

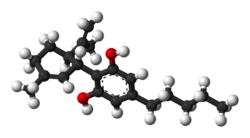

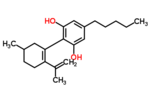

Cannabis plants produce a unique family of terpeno-phenolic compounds called cannabinoids, some of which produce the "high" which may be experienced from consuming marijuana. There are 483 identifiable chemical constituents known to exist in the cannabis plant,[53] and at least 85 different cannabinoids have been isolated from the plant.[54] The two cannabinoids usually produced in greatest abundance are cannabidiol (CBD) and/or Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), but only THC is psychoactive.[55] Since the early 1970s, Cannabis plants have been categorized by their chemical phenotype or "chemotype", based on the overall amount of THC produced, and on the ratio of THC to CBD.[56] Although overall cannabinoid production is influenced by environmental factors, the THC/CBD ratio is genetically determined and remains fixed throughout the life of a plant.[40] Non-drug plants produce relatively low levels of THC and high levels of CBD, while drug plants produce high levels of THC and low levels of CBD. When plants of these two chemotypes cross-pollinate, the plants in the first filial (F1) generation have an intermediate chemotype and produce intermediate amounts of CBD and THC. Female plants of this chemotype may produce enough THC to be utilized for drug production.[56][57]

Whether the drug and non-drug, cultivated and wild types of Cannabis constitute a single, highly variable species, or the genus is polytypic with more than one species, has been a subject of debate for well over two centuries. This is a contentious issue because there is no universally accepted definition of a species.[58] One widely applied criterion for species recognition is that species are "groups of actually or potentially interbreeding natural populations which are reproductively isolated from other such groups."[59] Populations that are physiologically capable of interbreeding, but morphologically or genetically divergent and isolated by geography or ecology, are sometimes considered to be separate species.[59] Physiological barriers to reproduction are not known to occur within Cannabis, and plants from widely divergent sources are interfertile.[47] However, physical barriers to gene exchange (such as the Himalayan mountain range) might have enabled Cannabis gene pools to diverge before the onset of human intervention, resulting in speciation.[60] It remains controversial whether sufficient morphological and genetic divergence occurs within the genus as a result of geographical or ecological isolation to justify recognition of more than one species.[61][62][63]

The genus Cannabis was first classified using the "modern" system of taxonomic nomenclature by Carl Linnaeus in 1753, who devised the system still in use for the naming of species.[64] He considered the genus to be monotypic, having just a single species that he named Cannabis sativa L.[a 1] Linnaeus was familiar with European hemp, which was widely cultivated at the time. This classification was supported by Christiaan Hendrik Persoon (in 1807), Lindley (in 1838) and De Candollee (in 1867). These first classification attempts resulted in a four group division:[65]

In 1785, evolutionary biologist Jean-Baptiste de Lamarck published a description of a second species of Cannabis, which he named Cannabis indica Lam.[66] Lamarck based his description of the newly named species on morphological aspects (trichomes, leaf shape) and geographic localization of plant specimens collected in India. He described C. indica as having poorer fiber quality than C. sativa, but greater utility as an inebriant. Also, C. indica was considered smaller, by Lamarck. Also, woodier stems, alternate ramifications of the branches, narrow leaflets, and a villous calyx in the female flowers were characteristics noted by the botanist.[65]

In 1843, William O’Shaughnessy, used "Indian hemp (C. indica)" in a work title. The author claimed that this choice wasn't based on a clear distinction between C. sativa and C. indica, but may have been influenced by the choice to use the term "Indian hemp" (linked to the plant's history in India), hence naming the species as indica.[65]

Additional Cannabis species were proposed in the 19th century, including strains from China and Vietnam (Indo-China) assigned the names Cannabis chinensis Delile, and Cannabis gigantea Delile ex Vilmorin.[67] However, many taxonomists found these putative species difficult to distinguish. In the early 20th century, the single-species concept (monotypic classification) was still widely accepted, except in the Soviet Union, where Cannabis continued to be the subject of active taxonomic study. The name Cannabis indica was listed in various Pharmacopoeias, and was widely used to designate Cannabis suitable for the manufacture of medicinal preparations.[68]

In 1924, Russian botanist D.E. Janichevsky concluded that ruderal Cannabis in central Russia is either a variety of C. sativa or a separate species, and proposed C. sativa L. var. ruderalis Janisch, and Cannabis ruderalis Janisch, as alternative names.[52] In 1929, renowned plant explorer Nikolai Vavilov assigned wild or feral populations of Cannabis in Afghanistan to C. indica Lam. var. kafiristanica Vav., and ruderal populations in Europe to C. sativa L. var. spontanea Vav.[57][67] Vavilov, in 1931, proposed a three species system, independently reinforced by Schultes et al (1975)[69] and Emboden (1974):[70] C. sativa, C. indica and C. ruderalis.[65]

In 1940, Russian botanists Serebriakova and Sizov proposed a complex poly-species classification in which they also recognized C. sativa and C. indica as separate species. Within C. sativa they recognized two subspecies: C. sativa L. subsp. culta Serebr. (consisting of cultivated plants), and C. sativa L. subsp. spontanea (Vav.) Serebr. (consisting of wild or feral plants). Serebriakova and Sizov split the two C. sativa subspecies into 13 varieties, including four distinct groups within subspecies culta. However, they did not divide C. indica into subspecies or varieties.[52][71][72] Zhukovski, in 1950, also proposed a two-species system, but with C. sativa L. and C. ruderalis.[73]

In the 1970s, the taxonomic classification of Cannabis took on added significance in North America. Laws prohibiting Cannabis in the United States and Canada specifically named products of C. sativa as prohibited materials. Enterprising attorneys for the defense in a few drug busts argued that the seized Cannabis material may not have been C. sativa, and was therefore not prohibited by law. Attorneys on both sides recruited botanists to provide expert testimony. Among those testifying for the prosecution was Dr. Ernest Small, while Dr. Richard E. Schultes and others testified for the defense. The botanists engaged in heated debate (outside of court), and both camps impugned the other's integrity.[61][62] The defense attorneys were not often successful in winning their case, because the intent of the law was clear.[74]

In 1976, Canadian botanist Ernest Small[75] and American taxonomist Arthur Cronquist published a taxonomic revision that recognizes a single species of Cannabis with two subspecies (hemp or drug; based on THC and CBD levels) and two varieties in each (domesticated or wild). The framework is thus:

This classification was based on several factors including interfertility, chromosome uniformity, chemotype, and numerical analysis of phenotypic characters.[56][67][76]

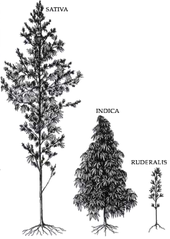

Professors William Emboden, Loran Anderson, and Harvard botanist Richard E. Schultes and coworkers also conducted taxonomic studies of Cannabis in the 1970s, and concluded that stable morphological differences exist that support recognition of at least three species, C. sativa, C. indica, and C. ruderalis.[77][78][79][80] For Schultes, this was a reversal of his previous interpretation that Cannabis is monotypic, with only a single species.[81] According to Schultes' and Anderson's descriptions, C. sativa is tall and laxly branched with relatively narrow leaflets, C. indica is shorter, conical in shape, and has relatively wide leaflets, and C. ruderalis is short, branchless, and grows wild in Central Asia. This taxonomic interpretation was embraced by Cannabis aficionados who commonly distinguish narrow-leafed "sativa" strains from wide-leafed "indica" strains.[82] McPartland's review finds the Schultes taxonomy inconsistent with prior work (protologs) and partly responsible for the popular usage.[83]

Molecular analytical techniques developed in the late 20th century are being applied to questions of taxonomic classification. This has resulted in many reclassifications based on evolutionary systematics. Several studies of random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) and other types of genetic markers have been conducted on drug and fiber strains of Cannabis, primarily for plant breeding and forensic purposes.[84][85][28][86][87] Dutch Cannabis researcher E.P.M. de Meijer and coworkers described some of their RAPD studies as showing an "extremely high" degree of genetic polymorphism between and within populations, suggesting a high degree of potential variation for selection, even in heavily selected hemp cultivars.[40] They also commented that these analyses confirm the continuity of the Cannabis gene pool throughout the studied accessions, and provide further confirmation that the genus consists of a single species, although theirs was not a systematic study per se.

An investigation of genetic, morphological, and chemotaxonomic variation among 157 Cannabis accessions of known geographic origin, including fiber, drug, and feral populations showed cannabinoid variation in Cannabis germplasm. The patterns of cannabinoid variation support recognition of C. sativa and C. indica as separate species, but not C. ruderalis. C. sativa contains fiber and seed landraces, and feral populations, derived from Europe, Central Asia, and Turkey. Narrow-leaflet and wide-leaflet drug accessions, southern and eastern Asian hemp accessions, and feral Himalayan populations were assigned to C. indica.[57] In 2005, a genetic analysis of the same set of accessions led to a three-species classification, recognizing C. sativa, C. indica, and (tentatively) C. ruderalis.[60] Another paper in the series on chemotaxonomic variation in the terpenoid content of the essential oil of Cannabis revealed that several wide-leaflet drug strains in the collection had relatively high levels of certain sesquiterpene alcohols, including guaiol and isomers of eudesmol, that set them apart from the other putative taxa.[88]

A 2020 analysis of single-nucleotide polymorphisms reports five clusters of cannabis, roughly corresponding to hemps (including folk "Ruderalis") folk "Indica" and folk "Sativa".[89]

Despite advanced analytical techniques, much of the cannabis used recreationally is inaccurately classified. One laboratory at the University of British Columbia found that Jamaican Lamb's Bread, claimed to be 100% sativa, was in fact almost 100% indica (the opposite strain).[90] Legalization of cannabis in Canada (as of 17 October 2018[update]) may help spur private-sector research, especially in terms of diversification of strains. It should also improve classification accuracy for cannabis used recreationally. Legalization coupled with Canadian government (Health Canada) oversight of production and labelling will likely result in more—and more accurate—testing to determine exact strains and content. Furthermore, the rise of craft cannabis growers in Canada should ensure quality, experimentation/research, and diversification of strains among private-sector producers.[91]

The scientific debate regarding taxonomy has had little effect on the terminology in widespread use among cultivators and users of drug-type Cannabis. Cannabis aficionados recognize three distinct types based on such factors as morphology, native range, aroma, and subjective psychoactive characteristics. "Sativa" is the most widespread variety, which is usually tall, laxly branched, and found in warm lowland regions. "Indica" designates shorter, bushier plants adapted to cooler climates and highland environments. "Ruderalis" is the informal name for the short plants that grow wild in Europe and Central Asia.[83]

Mapping the morphological concepts to scientific names in the Small 1976 framework, "Sativa" generally refers to C. sativa subsp. indica var. indica, "Indica" generally refers to C. sativa subsp. i. kafiristanica (also known as afghanica), and "Ruderalis", being lower in THC, is the one that can fall into C. sativa subsp. sativa. The three names fit in Schultes's framework better, if one overlooks its inconsistencies with prior work.[83] Definitions of the three terms using factors other than morphology produces different, often conflicting results.

Breeders, seed companies, and cultivators of drug type Cannabis often describe the ancestry or gross phenotypic characteristics of cultivars by categorizing them as "pure indica", "mostly indica", "indica/sativa", "mostly sativa", or "pure sativa". These categories are highly arbitrary, however: one "AK-47" hybrid strain has received both "Best Sativa" and "Best Indica" awards.[83]

Cannabis likely split from its closest relative, Humulus (hops), during the mid Oligocene, around 27.8 million years ago according to molecular clock estimates. The centre of origin of Cannabis is likely in the northeastern Tibetan Plateau. The pollen of Humulus and Cannabis are very similar and difficult to distinguish. The oldest pollen thought to be from Cannabis is from Ningxia, China, on the boundary between the Tibetan Plateau and the Loess Plateau, dating to the early Miocene, around 19.6 million years ago. Cannabis was widely distributed over Asia by the Late Pleistocene. The oldest known Cannabis in South Asia dates to around 32,000 years ago.[92]

Cannabis is used for a wide variety of purposes.

According to genetic and archaeological evidence, cannabis was first domesticated about 12,000 years ago in East Asia during the early Neolithic period.[5] The use of cannabis as a mind-altering drug has been documented by archaeological finds in prehistoric societies in Eurasia and Africa.[93] The oldest written record of cannabis usage is the Greek historian Herodotus's reference to the central Eurasian Scythians taking cannabis steam baths.[94] His (c. 440 BCE) Histories records, "The Scythians, as I said, take some of this hemp-seed [presumably, flowers], and, creeping under the felt coverings, throw it upon the red-hot stones; immediately it smokes, and gives out such a vapour as no Greek vapour-bath can exceed; the Scyths, delighted, shout for joy."[95] Classical Greeks and Romans also used cannabis.

In China, the psychoactive properties of cannabis are described in the Shennong Bencaojing (3rd century AD).[96] Cannabis smoke was inhaled by Daoists, who burned it in incense burners.[96]

In the Middle East, use spread throughout the Islamic empire to North Africa. In 1545, cannabis spread to the western hemisphere where Spaniards imported it to Chile for its use as fiber. In North America, cannabis, in the form of hemp, was grown for use in rope, cloth and paper.[97][98][99][100]

Cannabinol (CBN) was the first compound to be isolated from cannabis extract in the late 1800s. Its structure and chemical synthesis were achieved by 1940, followed by some of the first preclinical research studies to determine the effects of individual cannabis-derived compounds in vivo.[101]

Globally, in 2013, 60,400 kilograms of cannabis were produced legally.[102]

Cannabis is a popular recreational drug around the world, only behind alcohol, caffeine, and tobacco. In the U.S. alone, it is believed that over 100 million Americans have tried cannabis, with 25 million Americans having used it within the past year.[when?][104] As a drug it usually comes in the form of dried marijuana, hashish, or various extracts collectively known as hashish oil.[10]

Normal cognition is restored after approximately three hours for larger doses via a smoking pipe, bong or vaporizer.[105] However, if a large amount is taken orally the effects may last much longer. After 24 hours to a few days, minuscule psychoactive effects may be felt, depending on dosage, frequency and tolerance to the drug.

Cannabidiol (CBD), which has no intoxicating effects by itself[55] (although sometimes showing a small stimulant effect, similar to caffeine),[106] is thought to attenuate (i.e., reduce)[107] the anxiety-inducing effects of high doses of THC, particularly if administered orally prior to THC exposure.[108]

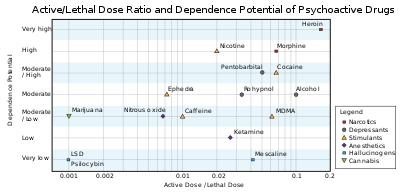

According to Delphic analysis by British researchers in 2007, cannabis has a lower risk factor for dependence compared to both nicotine and alcohol.[109] However, everyday use of cannabis may be correlated with psychological withdrawal symptoms, such as irritability or insomnia,[105] and susceptibility to a panic attack may increase as levels of THC metabolites rise.[110][111] Cannabis withdrawal symptoms are typically mild and are not life-threatening.[112] Risk of adverse outcomes from cannabis use may be reduced by implementation of evidence-based education and intervention tools communicated to the public with practical regulation measures.[113]

In 2014 there were an estimated 182.5 million cannabis users worldwide (3.8% of the global population aged 15–64).[114] This percentage did not change significantly between 1998 and 2014.[114]

Medical cannabis (or medical marijuana) refers to the use of cannabis and its constituent cannabinoids, in an effort to treat disease or improve symptoms. Cannabis is used to reduce nausea and vomiting during chemotherapy, to improve appetite in people with HIV/AIDS, and to treat chronic pain and muscle spasms.[115][116] Cannabinoids are under preliminary research for their potential to affect stroke.[117] Evidence is lacking for depression, anxiety, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, Tourette syndrome, post-traumatic stress disorder, and psychosis.[118] Two extracts of cannabis – dronabinol and nabilone – are approved by the FDA as medications in pill form for treating the side effects of chemotherapy and AIDS.[119]